Our next author, LeRoi Jones, will be the last contemporary Beat writer we'll be reading this term — our final two authors (Joyce Johnson and Hettie Jones) while closely-linked to writers like Kerouac, Ginsberg, Burroughs and Corso, didn't write their memoirs of the Beat era until long after the fact — and, for that mater, some question whether Jones is even a Beat writer in the first place.

As Donald Allen's groundbreaking 1960 anthology, The New American Poetry reveals, the Beats were just one of several sub-groups operating within the world of postwar experimental poetics, alongside the New York School, the San Francisco Poetry Renaissance group and the poets operating at North Carolina's Black Mountain College (who later navigated north to NYC after its close). LeRoi Jones, a multifaceted young writer — in addition to the poetry you'll read here, Jones was also an Obie-wining playwright, wrote a novel and short fiction, and also was a much-lauded music critic who penned a highly-influential volume on jazz, Blues People — was living and working in New York at the same time and both close friends with, and publisher of (through Totem Press and the journal Yugen, both of which he ran with his wife, Hettie) of members of all of these groups (Kerouac, Ginsberg and Corso from the Beats, Frank O'Hara and Kenneth Koch from the New York School, Gary Snyder from the SF poets, and Black Mountain writers including Paul Blackburn, Ed Dorn and Fielding Dawson), however he was never "officially" a member of any. Nonetheless, it's clear from the start of our reading in Transbluesency that the Beats are near and dear to him, and his writing, along with his wife's memoir, How I Became Hettie Jones, provides us with a unique perspective on the Beats and their times.

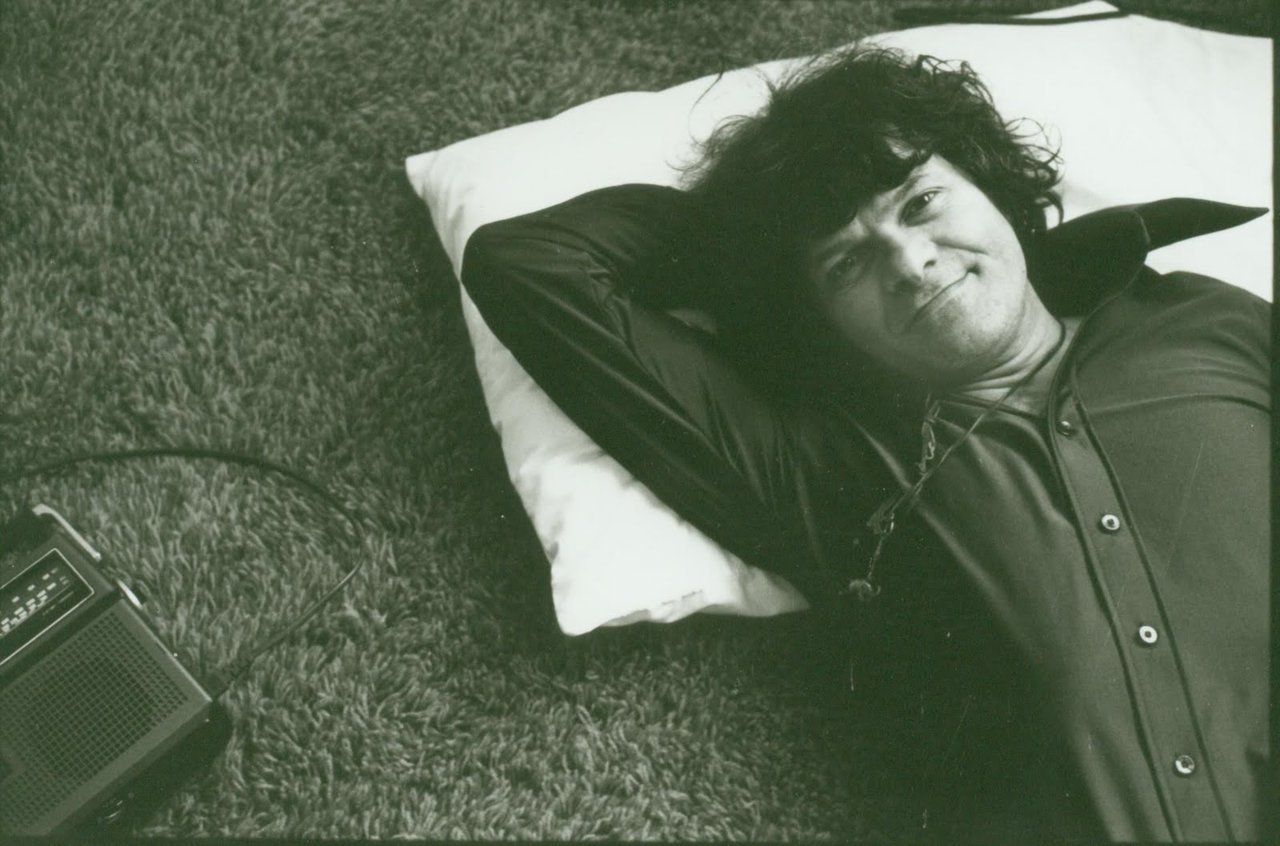

Born into a working class family in Newark, NJ (a city whose identity, both then and now, has been shaped by its large African-American popuation), the young and idealistic Jones studied religion and philosophy at Rutgers, Howard, Columbia and the New School (though he never earned a diploma) and read widely in contemporary literature and the arts. He joined the the Air Force, which gave him broader exposure to the world, but also an early reminder of the price one paid for his individuality, when the gunner sergeant was dishonorably discharged after he was discovered reading Communist writings. He'd eventually settle in New York City, where he'd meet and mingle with the city's young writers, marry his first wife, Hettie (a controversial interracial union in an era when such marriages were not only unrecognized, but also illegal in many states) and begin the publishing ventures mentioned above. Still guided by an intense interest in the political and social (particularly the fledgling civil rights movement), Jones would eventually move away from the friendships and artistic associations that would mark his early years. In 1960, he joined a delegation of artists and writers that traveled to Cuba as a show of solidarity, and as the decade unfolded, he'd find himself drawn into the Black Nationalism movement and the Nation of Islam, eventually (after the 1965 assassination of Malcolm X) going so far as to move to Harlem, leaving his wife and two daughters behind, sever many of his associations with former friends, and change his name to the one on the cover of your book (and the one he went by until his death this January): Amiri Baraka. While his political passions and his association with the Nation of Islam would eventually fade slightly, and he'd express regret for some of his actions, he remained (and remains) a defiant figure in America's literary and cultural scenes, a tireless advocate for a uniquely black aesthetics, and an adventurous and formally inventive writer.

While, like many of our previous authors, Jones/Baraka continued to write beyond the Beat heyday, we'll more narrowly confine our focus to his earlier output, with a few selected later works thrown in. Here's the breakdown for our two classes:

Tuesday, Nov. 4: Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide Note (1961) and The Dead Lecturer (1964)

Tuesday, Nov. 4: Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide Note (1961) and The Dead Lecturer (1964)

- Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide Note (5)

- Hymn for Lanie Poo (6)

- In Memory of Radio (15)

- Look for You Yesterday, Here You Come Today (17)

- To a Publisher . . . Cut-out (22)

- Way Out West (29)

- The Bridge (31)

- Symphony Sid (36)

- The New Sheriff (43)

- Notes for a Speech (48)

- As a Possible Lover (53) MP3

- Balboa, the Entertainer (54)

- A Contract (For the Destruction and Rebuilding of Paterson (56) MP3

- A Poem for Neutrals (58)

- An Agony. As Now (60)

- A Poem for Willie Best (62)

- Short Speech to My Friends (72) MP3

- A Poem for Democrats (77)

- The Measure of Memory (78)

- Footnote to a Pretentious Book (80)

- Rhythm & Blues (I (82)

- Black Dada Nihilismus (97) MP3 / DJ Spooky mix: MP3

- A Guerrilla Handbook (101)

- Political Poem (107)

- A Poem for Speculative Hipsters (110) MP3

- Three Modes of History and Culture (117) MP3

- A Poem Some People Will Have to Understand (120) MP3

- The People Burning (122) MP3

- The New World (127)

- Tone Poem (131)

- Numbers, Letters (136)

- Red Eye (138)

- Return of the Native (140)

- Black Art (142)

- Poem for HalfWhite College Students (144) MP3

- American Ecstasy (145)

- History on Wheels (151)

- Real Life (155)

- PennSound's Amiri Baraka author page

- The New Yorker praises Baraka's jazz writing

- The New York Times' obituary for Baraka

- Questlove writes on Baraka (also in the Times)

- "Baraka in 2010" — a wide-ranging interview with the poet in Jacket2

- The Poetry Foundation gathers responses to Baraka's passing

- Chris Funkhouser reminisces on his work recording Baraka in a Jacket2 commentary

- Kristen Gallagher writes about Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide Note in Jacket2

- PoemTalk #20 on Baraka's "Kenyatta Listening to Mozart"