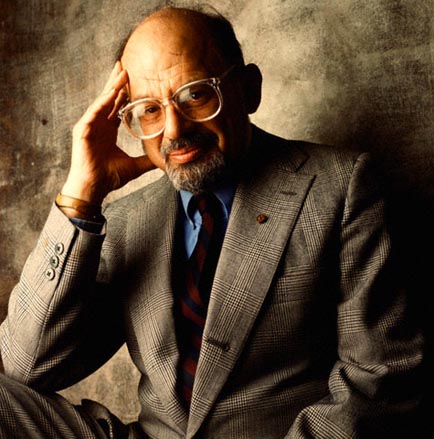

There's not much to say and very little to weep for at the end of Ginsberg's life. The most important lesson here is the ability to adapt, to hybridize, to change as the times change — Ginsberg had it, Burroughs had it, even Cassady had it, but unfortunately Kerouac did not, and that's why our last memories of him are as a bitter, bloated drunk, while the rest were lively and engaged until the end.

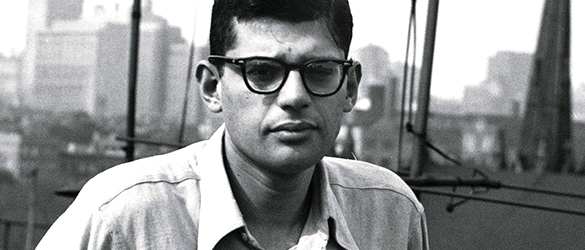

All of the themes that we've traced throughout Ginsberg's life continue through his last decade. In particular, I wanted to address his musical interests as being particularly evocative of his ability to grow and change. In last week's readings, we see the hopefulness of the 60s give way to Nixon-era spiritual and political malaise, followed by the youthful rebellion of punk rock, and Reagan's conservative stranglehold in the 80s bringing us to a reemergence of socially-conscious youth in the 1990s. These evolutions reflected in Ginsberg's work, in the ideologies he espoused, and see him happily embraced each new mode, whether that would find him on tour with Bob Dylan or sharing the stage with the Clash. The young Ginsberg who celebrated seeing the Beatles in concert in "Portland Coliseum" would have close ties to the world of popular music until the end of his life, most notably his mid-90s collaboration with Paul McCartney, Lenny Kaye and Philip Glass, "The Ballad of the Skeletons."

Ginsberg evolved to the very end. In 1996 Ginsberg took part in a discussion/interview with Beck, published in the Buddhist magazine Shambhala Sun with the unfortunate subtitle, "A Beat/Slacker Transgenerational Meeting of Minds." The two had met a year-and-a-half earlier in New York, backstage at the Lollapalooza festival. He also started talks with MTV about doing an episode of their Unplugged series with musical accompaniment by Bob Dylan, Philip Glass, Paul McCartney, and Patti Smith. At the same time, Ginsberg acknowledged that the world was quickly moving beyond him. In a 1996 interview with Hotwired (an online web journal related to Wired magazine), he offered his response to seeing the internet for the first time: "Thank God I don't know how to work this!"

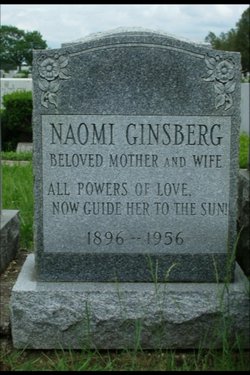

Diagnosed with terminal liver cancer in early 1997, he greeted this latest transition with great enthusiasm, calling friends to say farewell even as he lamented all of the things he'd never be able to do. On April 5th, surrounded by friends and family in his modest NYC apartment, he breathed his last.

Here are our final Ginsberg readings, with audio when available:

- A Public Poetry (869)

- Maturity (872)

- I'm a Prisoner of Allen Ginsberg (882)

- Prophecy (915)

- Sphincter (950): MP3

- Cosmopolitan Greetings (954)

- Personals Ad (970): MP3

- May Days 1988 (979)

- CIA Dope Calypso (996): MP3

- Numbers in U.S. File Cabinet (Death Waits to be Executed) (982)

- Return of Kral Majales (984): MP3

- After the Big Parade (1010): MP3

- After Lalon (1019): MP3

- Put Down Your Cigarette Rag (Don't Smoke) (1029): MP3

- Autumn Leaves (1046)

- New Democracy Wish List (1063)

- Tuesday Morn (1074)

- "Put Down Your Cigarette Rag (Don't Smoke)"

- New Stanzas for Amazing Grace (1080): MP3

- The Ballad of the Skeletons (1091): MP3

- Richard III (1128)

- Death and Fame (1129)

- Dream (1159)

- Things I'll Not Do (Nostalgias) (1160)

Personals Ad

Put Down Yr. Cigarette Rag (Don't Smoke)

Ginsberg's video (shown on MTV's "Buzz Bin" and at the Sundance Film Festival) for "The Ballad of the Skeletons," directed by Gus Van Sant and featuring musical accompaniment by Paul McCartney, Lenny Kaye and Philip Glass

MTV's obituary for the poet

Finally, though it can't be embedded: experimental filmmaker Jonas Mekas' Scenes from Allen's Last Three Days on Earth as a Spirit documents the scene just before and after Ginsberg's passing in 1997, including conversations with those who've gathered to send their friend off [note: this can be a challenging and emotional film to watch]

And some optional readings: