For your final essay, you'll respond to one of the following prompts, which will allow you to analyze and synthesize our readings throughout the term through one of several broad frames (mortality, gender, nationality, authority and spirituality). Within each question, you'll be required to decide upon a number of key ideas/concepts/characters (usually three) and then explore each with appropriate complexity, bringing a wide array of textual evidence into play to support your points. Before further discussing the nuts and bolts of your finals, here are the prompts:

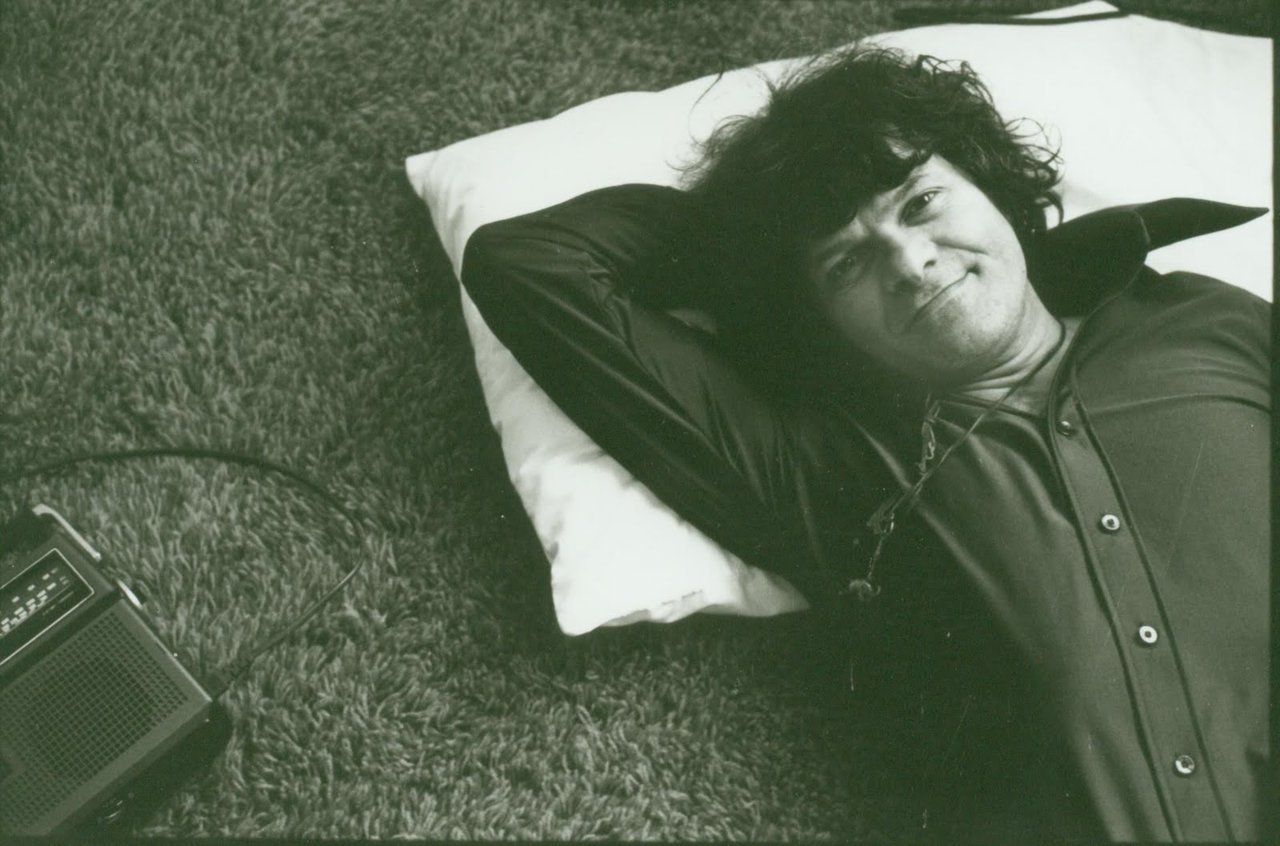

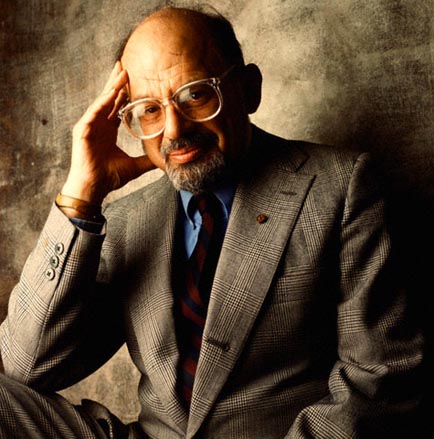

- In Kerouac's famous appearance on The Steve Allen Show, he observes that "I wrote [On the Road] because we're all going to die," while Ginsberg, mourning his father in "Don't Grow Old" muses, "What's to be done about Death? / Nothing, nothing." All of our authors' formative years have been marked by the loss of loved ones (Kerouac's brother and father, Ginsberg's mother, Burroughs' wife, Corso's mother) and they've witnessed the premature deaths of many friends and colleagues (including Neal Cassady, Kerouac himself, Kells Elvins, Louis Ginsberg, Billy Burroughs Jr., Chogyam Trungpa, Elise Cowen, etc.). How do these experiences of loss frame their lives and writing? How does it motivate them or alter their perspectives on living? Does it make them more willing to avoid complacency or take more risks? How do these attitudes change over time and in what ways do the authors deal with their own mortality?

- Throughout the quarter, we've lamented both the absence of female authors and lead characters in the various Beat Generation writings we've been reading, along with the general attitudes exhibited towards women, which have ranged from indifference and neglect to outright misogyny. We're addressing this issue now with readings from Joyce Johnson and Hettie Jones, who offer their own stories from the time period, documenting their search for ideological, spiritual, literary and sexual freedom, along with the pitfalls and benefits of living their lives outside of society's expectations for young women. Guided by these lessons, I'd like you to go back into our earlier readings and explore three female characters you find there — some potential candidates: Marylou, Evelyn, Helen Hinkle, Terry, Mardou Fox, Naomi Ginsberg, Joan Vollmer Burroughs, Elise Cowan — comparing their experiences with the first-person testimonies of Johnson and Jones. In what ways are they liberated and how are they degraded by their male partners and society at large? Who emerges relatively unscathed and who pays the greatest costs?

- From Sal Paradise's controversial desire to be anything but white in On the Road to the our authors' great appreciation for non-white cultural artifacts (from bebop jazz to Zen Buddhism), a key hallmark the Beat Generation is its transgression of traditional racial boundaries. Explore the complexities of this phenomenon as embodied by our readings throughout the semester. What specific affinities do our authors demonstrate? What risks do they take for the sake of these desires? In what ways do they show a greater empathy for other races than their fellow citizens, and what (well-intentioned) mistakes do they make? How do the Beats address racism in their writings, and in what ways might their own marginalized identities foster a greater understanding? Interracial relationships — from Leo and Mardou in The Subterraneans to Hettie and LeRoi Jones — are particularly revealing and might form a foundation of your argument.

- The Beat Generation is an essentially American literary movement, and many would argue, ultimately a patriotic movement — celebrating the heart and soul of American life and exploring the true breadth and diversity of its populace along with its natural grandeur — even if its authors might not agree wholeheartedly with mainstream American culture or morality. That having been said, it's curious that all of the authors we've read have benefited greatly from time spent outside the United States, and many of our readings have either taken place in international locales (including Mexico, Tangiers, Paris, London, Wales, South America, India, Cuba and even Interzone) or were written there. Analyze the tensions between the foreign and domestic in Beat literature: how are places like Mexico City and Tangiers depicted by the Beats, and why are they so attractive to them? What dangers exist in these places, and what freedoms can be found there that aren't readily available in America? How does the Beats' interaction with these cultures and locales relate to their exploration of America itself and its various counter- and sub-cultures, its ethnic groups, its artistic scenes? Are there places within America where similar freedom might be found? Is the ideal base of operations for the Beats within or outside of America, and why?

- "Prison is where you promise yourself the right to live," Kerouac observes in On the Road and all of our authors this term have had run-ins with the law — from Kerouac's arrest as an accessory to the David Kammerer murder to Burroughs' accidental shooting of his wife, Ginsberg's charges related to stolen goods that eventually saw him committed to Pilgrim State, Corso's numerous juvenile incarcerations, and Baraka's arrest during the Newark Riots — and partaken in various illegal activities. Explore the Beats attitudes towards authority and criminality as demonstrated in their writings: What are their criticisms of mid-century society's laws and culture of repression? How do their address institutionalized injustice and personal freedom? What are the benefits of living outside of the law and what liabilities and anxieties does that foster? What hypocrisies do they reveal in police, politicians and the military? You're free to respond to this question in a more general fashion or focus exclusively on a single sub-topic such as drugs, free speech/censorship, social injustice, war/pacifism, etc.

- Spirituality — whether Catholicism, Hinduism, Buddhism or a more general Humanist practice — is at the heart of the Beat Generation aesthetic, from the early strains of Ginsberg's "Footnote to Howl," where he declares the holiness of everything (in graphic catalogued detail) to the authors' preparation for death. Consider the role of faith and spirituality within this quarter's readings, as both philosophical worldview and personal practice, paying special attention to the ways in which differing religious perspectives are intermingled in the texts. How do the Beats differentiate their faith from that of mainstream America and what critiques of organized religion (and/or the actions committed in its name) do they offer. In what ways do they use their writing as a vehicle to provide readers with practical instruction in faiths other than their own? Finally, in a more general sense, how would you define Beat spirituality?

Your final essays should be a minimum of six (6) pages (and by six pages, I mean that the text of your essay itself makes it to the very bottom of the the page, or better yet onto a 7th), and written in MLA style (including a proper header, parenthetical in-text citations and a works cited list at the end), double-spaced in 12-point Times New Roman, no tricked-out margins, etc. You'll e-mail your papers to me no later than 5:00 PM on Monday, December 8th. Because e-mail is an imperfect delivery medium and the UC system is prone to collapse, take note that I'll reply to each paper received, letting students know that it's arrived safely, so if you don't receive that e-mail, get in touch with me, and should you have any questions or concerns prior to the deadline, don't hesitate to drop me a line.

Also, please don't forget that tardy papers will be docked a full letter grade for every day they're late and that papers that are less than the stated limit of six full pages will automatically receive an F. Finally, I will not permit block quotes for this essay — whittle down your quotations to the essential information and make use of summary and paraphrase when necessary.

While six pages seems like an endlessly long paper, I can assure you that it's not really a lot of space to discuss these topics in great depth, therefore I wholeheartedly encourage you to dispense with any and all filler, including bloated rhetoric and lengthy five-paragraph-style introductions that ultimately say very little while taking up a lot of word count. Don't hover over the surface of the issues — dive right in and get to the heart of your argument from the start. I also recommend that unless you have compelling reasons to do otherwise, organize your essay around the topics (characters/techniques/etc.) you've chosen to discuss, rather than proceeding chronologically or dealing with each author individually, and also that you write through the source texts themselves, as demonstrated in the "Making Effective Arguments" post I put up at the start of the term. You do not need to do outside research for this assignment, and you should avoid lengthy explications of the authors' biographical details or summaries of the plots of texts outside of what relates directly to the points that you are making. Presume that the person reading your paper has read all of the texts you reference (because he has!). Finally, make sure that you are following the conventions of MLA formatting (which can be found in numerous places on the internet).